By Lisa Lim, J.D., If/When/How Development Director

By Lisa Lim, J.D., If/When/How Development Director

February was a difficult month for me. I’d only caught my breath after the insurrection at the Capitol; my 80-year-old mother and her friends were scrambling to get vaccination appointments; and a new, less hostile administration gave me cause for a bit of optimism for 2021. But then new reports of violent attacks on Asian elders and Asian-owned businesses in the San Francisco Bay Area started trickling in, sending what seemed like a ripple effect across the country. Then, last week, more terrible news: in Atlanta, eight people were killed in targeted, racist attacks at massage parlors; six of the victims were Asian women.

Last May, my colleague Jon Wong wrote about how the pandemic exacerbates anti-Asian sentiments. At the time, the former president had falling polls over his lackluster response to the pandemic. To distract from his failures to act on the pandemic and to amplify xenophobia, he started referring to COVID-19 as “kung flu” and the “China virus.” As the months passed and the initial waves of anti-Asian violence seemed to subside, I thought anti-Asian sentiment had plateaued and was lulled into a false sense of calm. But now that the racism and violence against our communities has become more visible and purportedly escalated, I feel the need to address anti-Asian racism as an urgent reproductive justice issue.

If there is anything that I’ve learned from my work at If/When/How, it’s that we won’t make progress on issues central to human rights such as racial justice and reproductive justice until we address structural oppression and call out our own biases. Our country has a legacy of racial scapegoating rather than taking the time to examine how our capitalist system and political institutions are set up to benefit a small, privileged fraction of our population, leaving the working class and marginalized communities to fight one another for scraps. Unfortunately, when this racist scapegoating narrative is amplified by people in power, it becomes internalized by the people who hear its messaging.

It’s important to recognize how this moment is rooted in a long legacy of anti-Asian racism and violence we’ve experienced throughout our history in the U.S., and how our position in the racial hierarchy of this country makes this silence and marginalization possible. From the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit, Asians have been convenient scapegoats blamed for job loss, trade imbalances, or the source of disease. On one hand, we are the “yellow peril,” a threat to the state that needs to be expelled, and on the other hand, we are the “model minority,” a convenient foil to other communities of color fighting for racial equity. The first waves of Chinese, Japanese and Filipino immigrants were brought in as cheap and expendable manual labor and denied the ability to establish families, own property, or gain citizenship. The Page Act of 1875 was the first law restricting immigration into the U.S. and barred entry to women of Chinese and other East Asian descent. This kept families apart and denied these early immigrants the ability to establish roots in this country. It characterized Chinese and East Asian women as “immoral” and launched the practice, which continues to this day, of restricting immigration based on sexuality.

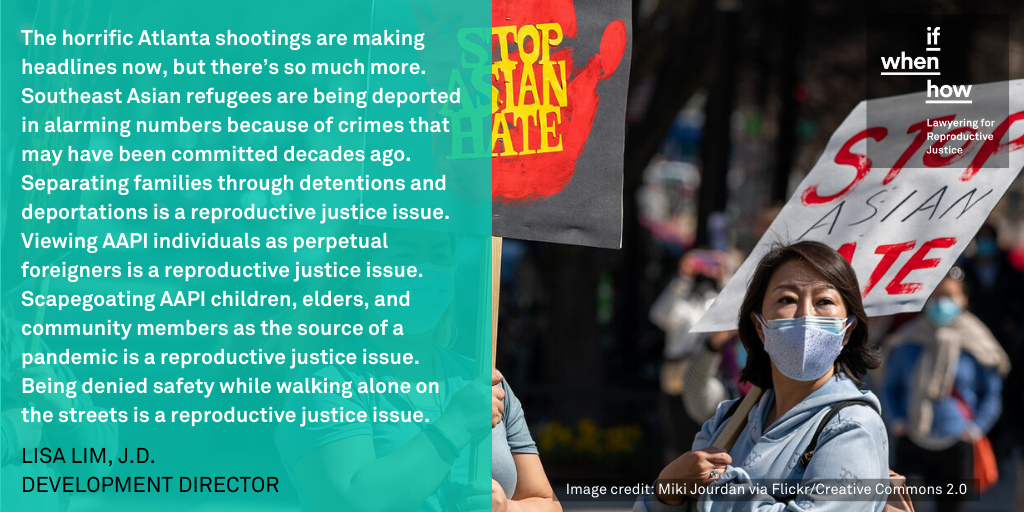

Today, we are witnessing how these policies are currently playing out in our communities. The horrific Atlanta shootings are making headlines now, but there’s so much more. Southeast Asian refugees are being deported in alarming numbers because of crimes that may have been committed decades ago. Separating families through detentions and deportations is a reproductive justice issue. Viewing Asian American and Pacific Islander individuals as perpetual foreigners is a reproductive justice issue. Scapegoating AAPI children, elders, and community members as the source of a pandemic is a reproductive justice issue. Being denied safety while walking alone on the streets is a reproductive justice issue.

Ultimately, the rise in anti-Asian hate incidents and the lack of awareness around our issues are both hallmarks and symptoms of white supremacy. A statement that resonates with me in this instance is in the definition of reproductive justice as shared by SisterSong: “All oppressions impact our reproductive lives; RJ is simply human rights seen through the lens of the nuanced ways oppression impacts self-determined family creation. The intersectionality of RJ is both an opportunity and a call to come together as one movement with the power to win freedom for all oppressed people.”

So where do we go from here? AAPIs are neither the model minority—a silent, apolitical monolithic mass—nor are we the perpetual foreigner, here to steal jobs and spread disease. We need more widespread awareness and education on AAPI issues and our histories. AAPI victims and survivors need to be seen, heard, and validated. Harms against our community must be met with public condemnation. We have to stand together against white supremacist thinking and actively fight against internalizing those perspectives. When we can be accountable to one another and have difficult conversations about racist systems that benefit from keeping us separated and silenced, our communities grow stronger and better equipped to chip away at structural racism.

I’m asking that folks show up and see us, hear our stories, and listen with empathy. Let’s work together, using our reproductive justice lens, to dismantle this country’s racist caste system. We are at a crucial moment with so many aware enough, loud enough, and bold enough to make real change happen.